Container Architecture on Display at Container City

Container architecture has been an interest of mine since it first popped up on my scope a few years back. While visiting the city of Puebla, Mexico I noticed a curious attraction called "Container City".

What is Container City?

Conveniently close to the pyramid at Cholula a trip to Container City would allow me to see architecture on opposite ends of the spectrum in one day. Container architecture is modern. Pyramid construction is ancient. Pyramids are grand, public affairs. Container buildings are small and private. How could an architecture buff resist such a contrast at the expense of one little excursion?

There wasn't much tourist information on Container City. It was billed as an experiment in green architecture. I didn't even have an address. What I had was a link to a map, which gave the street location in San Andres Cholula, an outlying town to the sprawling Puebla.

A half hour and an exploitive cab fare later I was in front of the what appeared to be a commercial strip mall designed by hippies who hadn't quite recovered from that last mushroom trip.

There were probably about 20 separate buildings. It was difficult to say because several were connected with walkways and common walls. Most, perhaps all, were businesses, although a few may have been residential in nature.

The buildings that formed the face of the community were either bars or restaurants. It wasn't exactly in the commercial center of town, so business was light at 2 in the afternoon.

It was decidedly industrial in its presentation. Some of the buildings were professionally finished. A few seemed to have been DIY projects.

While I had hoped to see houses what I found were not far different from the way container houses would have been constructed.

Design and Container Architecture

The container homes and business in Container City seem a little harsh in their presentation. When you are used to seeing homes in the Midwest and East Coast these are too boxy. When you are used to seeing the stuccoed walls of the Southwest, the corrugated metal seems too mechanical and unnatural.

On the other hand, when you are used to seeing the unfinished concrete block structures that dominate much of Mexico, the transition to shipping container architecture doesn't seem like quite a leap.

There is a fair variety in the way the containers are stacked and joined. Shipping containers have reinforced corners with holes and posts that mate to each other so they won't easily shift during transport. But shipping container homes often take liberties with the way the are stacked. The containers can be offset, or turned 90 degrees, or even placed on end.

Perhaps the biggest objection to shipping containers as structures is their corrugated skin. It's very industrial, but it can give a collection of such structures the feel of a depot, or junk yard. Its just not what we are used to. While the citizens of Container City have generally embraced the industrial look I did find two examples where some effort was made to soften that look

In one case a restaurant had covered a wall with a bamboo fence. It was inexpensive and effective. For a small price there was a remarkable transition.

In another case one wall was covered with a flowering vine. As one who loves flowers I wish there had been more of this. Vines are God's way of helping us obscure the mistakes of architects. Even architects use this trick. And if there aren't mistakes vines can provide a beautiful change of color and texture. I love a well-made brick wall, but a brick wall covered in ivy is even better.

One interesting device in shipping containers is the door on the loading end. While the buildings in Container City often had doors added in other places it was very common to see the end doors employed as an architectural feature, to be dispayed and used in creative ways.

Where is Container Architecture Appropriate?

While container houses can be built anywhere, they are more appropriate to some locations than to others.

Puebla, Mexico is temperate, but almost semi-tropical. It is high altitude, which keeps it from the extreme heat of coastal Mexico. In January it might get down to freezing. In some years it might not ever reach freezing, but most of the year the nights and the days are pleasant. This helps sell the case for container architecture, as the conductive nature of metal can make a container an oven in a hot summer, and a freezer in a cold winter. Of course you can insulate the metal, but you are having to work against the nature of the siding. Brick, wood, and earth are much better choices based strictly on their thermal properties.

That doesn't mean you can't build container houses in Saudi Arabia, or Alberta, Canada. You will just have to spend more money and thought in reducing the heat gain and heat loss. Eventually that extra cost might eat into container architecture's big cost advantage.

Wherever you build you probably need to something to mitigate conduction of heat into or out of the containers. Usually this will mean insulating either inside or out. Unfortunately this partially negates the container's advantage of having walls already in place.

In Container City every building had the original skin on the outside. The buildings I saw had interior walls, usually of sheetrock, and I assume they were insulated. However some of the bars and restaurants were open walled, so there wasn't much point in insulating these.

What are the Advantages of Container Architecture?

Where container houses shine is their building block capabilities, the ease of construction, the cost of materials, their scalability, and the durability of the final product.

Container City is a showcase for what can be done in container architecture. Affordable housing is a big problem throughout the world, and container houses should be a part of the solution.

Let's consider these advantages as we look at how they are used in the container architecture of container city.

Building Blocks for Affordable Houses

As I looked around Container City I noticed that quite a few of the container buildings were two stories. Shipping containers are designed to be stacked. On trucks they are one high. On trains they are usually two high, but on ships they are often stacked seven or eight deep. This ability to build vertically makes them appropriate even for densely populated areas where land is expensive.

Compare this to adobe, rammed earth, or earthships where building codes or physics will prevent you from going over two stories high.

The building block nature of containers also means they are scalable. If you need to add a bedroom, just attach another container off the side, or add it on top. Tying another container into the structure is a lot easier than adding on to a wood home, because each container is structurally sound within itself. In most cases you won't have to add structural supports, or temporarily shore up the opening needed to tie in new construction with the existing building.

It is this structural self-sufficiency that makes container houses so appealing to do-it-yourselfers. Build a frame house wrong and it sags. Build masonry incorrectly and the wall falls down. But a mishap with a container is most likely only going to result in a dented container.

The Simple Construction Techniques of Container Architecture

There are two basic construction techniques evident in the container architecture of this particular experiment in alternative housing. With containers your two basic means of forming your space are cutting and welding. In the buildings I saw there were entire walls cut away and the opened up containers were welded together to form larger spaces.

Exterior walls were replaced with sliding glass doors, or left open to form a kind of patio.

Metal poles, corrugated sheet metal, gratings and side rails were used to extend the space, creating patios, walkways, awnings and roofs. As is not uncommon in Mexico, tarps often provided additional cover.

Your principle tools will be cutting torches, cutting and grinding wheels, welders, and the various jacks, forklifts and lifting devices need to properly position the containers.

The only one of these that requires high skill is welding. While it might take a lot of instruction and practice to become a skilled welder, much of the welding needed can be done by someone with little training. A skilled welder can weld seams free of any voids, capable of holding pressure, and pretty to look at. But simple welds are all that is needed in most cases. Where skill is lacking adding more weld can make up the difference. Where advanced welding is need then you can call in the pro, but that won't be the majority of the welds.

Material Costs for Container Houses

With container architecture finishing your interior will probably cost much more than the structure itself, but that depends on how refined a finish you are looking to create.

The container itself is usually used, and often nearing the end of its useful life. Dents and some rust are the price paid for getting inexpensive material.

The shipping container industry is much larger than the current market for shipping container houses. That means for the foreseeable future the alternative housing market can rely on the castoffs of the shipping industry. The biggest expense will probably be trucking them from the shipping yard to your lot, but they are easily transportable.

Things like plumbing, wiring, insulation and won't be cheaper in a container home. Windows and doors will set you back just as much as with a stick built home, unless you opt for inexpensive alternatives.

The cool thing about container architecture is that it doesn't really have to look like a finished suburban home. If you go with industrial chic or steampunk, industrial castoffs might provide for functional alternatives to many of the fixtures a house needs.

Tough and Durable - Avoiding Rust

Shipping containers are built tough. They are heavy gauge steel, so that they can withstand being picked up by cranes and having many layers of full shipping containers stacked above them.

Those properties should enable them to endure as long or longer than traditional materials, if simple precautions are taken to prevent rust.

Rust is the big threat to container houses. Container architecture needs to account for this and ensure that water doesn't collect, that it is properly protected with paint, and that dissimilar metals are not used that can result in galvanic corrosion.

Lets talk about some of these issues.

Water in any form can cause rust. Shipping containers will generally shed rainwater, but they aren't designed to last hundreds of years. The shipping industry uses them for a few decades and then replaces them. For your house to last hundreds of years you might need to improve upon the design of your container.

Testing for how well your container sheds water is as simple as watering it down with a garden hose and seeing where water collects. If poos of water form then it might be appropriate to add a roof over the top. This can be as simple as adding corrugated sheet metal with one edge propped up giving it additional slope.

Anywhere you add crossmembers that interfere with how the water flows off the walls you run the risk of trapping water. A window inserted into a wall is one place where you might have this problem. Add a little dust and condensation and over time you can end up with wet mud keeping parts of your container permanently wet. A good design will ensure water doesn't get trapped.

It isn't just rain that provides the moisture. Humid air and cold mornings equals condensation. A little condensation everyday and moisture traps equals rust problems. A good paint job will help, but if water is collecting it won't help long.

One option is to prevent condensation by coating the exterior with an insulating foam or an asphaltic material similar to automotive undercoating. It isn't just that the water is separated from the metal. It keeps the metal from getting as cold as the outside air, so condensation doesn't form. Unfortunately it probably isn't going to look as good as the smooth metal coated with paint.

What we see in Container City is the use of standard industrial paint. It is dry part of the year, but it can be humid in the rainy season. However, in Puebla, when it is most humid it also has the warmest nights, so humidity isn't as big a problem as you would find elsewhere.

Another source of corrosion is the use of dissimilar metals in construction. This won't be a problem with the container itself. The problem will usually show up where a bolt or bracket has been welded or bolted onto the shipping container.

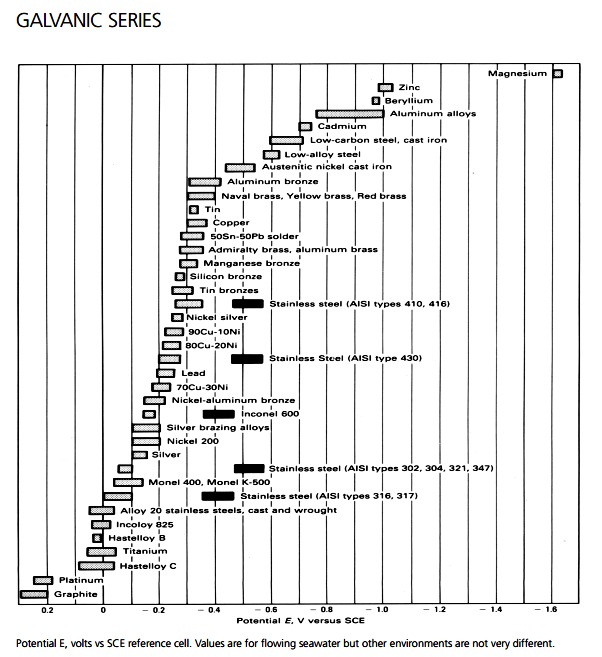

Metals have a property called an electrode potential, and if my memory serves me, it is a measure of the ease with which it gives up an electron. Two different metals will have two different potentials, measured in volts. That difference in potentials for the two metals becomes a problem when it is greater than 0.1 volts. As a practical matter that limit is more like .15 volts in humid conditions and .5 volts in dry conditions.

When wet, one metal will give up ions to the other metal. The metal giving up the ions will eventually corrode away. The corroding metal is called the anode and the receiving metal is called the cathode.

As long as the anode is much larger than the cathode there might not be any problem. For instance if you have a copper roof held in place with stainless steel screws the copper roof is the anode. Since there is so much more roof than screw the copper can afford to lose the few ions it will give up to the screws. Reverse the situation, where the fastener is the anode, and you end up with the fasteners quickly corroding.

So how do you know the electrode potential of the various metals? This can be a problem. With the containers themselves you will probably have to assume that it is carbon steel and use a standard figure from a chart of electrode potentials off the internet. For anything you buy commercially they should be able to tell you the grade of metal used and you can use that information to get an accurate figure for that material. For castoffs you will probably have to content yourself with deciding the general type of metal (brass, copper, zinc, stainless steel, etc).

For an example, using the chart below, what if you wanted to attach an aluminum balcony to the outside of your container? The sixth line down shows that low-carbon steel has a potential of somewhere between -.6 volts and -.7 volts, while aluminum is hanging out at around -.8 to -1.0 volts. Sounds like a potential disaster. What you can do in such a case is to use some kind of non-metallic separator between the container and the aluminum, but a cheaper choice is just to make your balcony out of a carbon steel similar to the shipping container.

A chart showing the potential of various metals

A chart showing the potential of various metalsWhile this problem of dissimilar potentials causes all kinds of grief when designing metal structures it also provides an opportunity.

You can use what is called a sacrificial anode to protect your container homes. In this scheme you deliberately connect a large mass of zinc to the container. Usually this is done with a copper wire connecting the container to a buried block of zinc. The zinc, sitting in the wet ground is constantly corroding, but in the process it is protecting the container from corroding.

This will last many years, perhaps decades, whereupon the anode will need to be replaced. They do this for pipelines and they have one part of the wire above ground at a test station. Here they can hook up a volt meter to the wire and measure the current. If no current registers then it is time to replace the anode.

Besides zinc, aluminum and magnesium anodes are available. You can buy them commercially or make your own from ingot or scrap materials. I have found ingot available on Amazon, and local metal dealers may carry it.

I have no idea if any cathodic protection was used for the housing at Container City. Generally something like this isn't visible, and if it was it would look like a grounding wire for the electrical system.

An Aesthetic Critique

While Container City is interesting, there is a certain ramshackle flavor to it. In one sense I feel that the experiment hasn't gone far enough, and in another that it is too different from what it normal.

Container architecture has the potential to go many different directions, but here they stuck with the basics. Other than one container on end there wasn't much creative or new in the way they put together their buildings.

At the same time there wasn't much beauty here. There were bright colors, but also much that was dirty and disheveled. It was a step up from a shanty town, but a step down from the stuccoed exteriors of the better Mexican neighborhoods. The best you could really say was that it was on par with the unfinished block exteriors that are too common in many places in Mexico.

Container City proves that buildings can be made from containers, and perhaps the cost savings makes that appealing, but it doesn't make a strong aesthetic case for container architecture.

The Future of Container Architecture

Despite my disappointment with Container City t is my sincere hope that container architecture takes off. I even hope I can do my part. It can provide inexpensive housing, and it is a great way to recycle.

I'd much rather see a container home than a mobile home. I have always found mobile homes to be aesthetically unappealing. Worse, they cause me pain and anguish.

Perhaps it is because they try too hard to be like a normal home but fall so short. The thing I like about container homes is their ability to be a canvas for the creative. A man who makes a container home can go so many directions. While I encourage architects to take container's seriously I love the fact that container architecture can be easily practiced by those who aren't architects.

The mass-production of mobile homes makes them cheap, but it also makes them bland. Likewise the cookie cutter nature of the tract homes on the lower end of the market usually means boring. With container architecture a surprise hides behind every corner.

As usual the enemy of this opportunity for innovation is the codes and zoning regulations that make it either too expensive or impossible to create a community of creative homes. It doesn't fit into the suburban mold. Developers don't know what to do with it.

So let us hope that more Container Cities will pop up, and this type of haven for artistic expression can find its way into the hearts of those who run our cities, finance our homes, and develop our neighborhoods.

Long live container architecture.

Container Architecture - To Top of Page

Please!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.