John Ruskin: The Seven Lamps of Architecture

In 1849 John Ruskin published an article called The Seven Lamps of Architecture. In this he distills the essence of the Gothic Revival down to seven “lamps”. They are as follows:

- Sacrifice

- Truth

- Power

- Beauty

- Life

- Memory

- Obedience

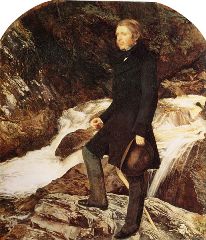

These aren’t guides for how to create a building. These are the foundations for building with integrity, at least to the mind of John Ruskin. Ruskin himself was a theoretician and a critic more than an artist or architect, but he was also a great writer and his writings and lectures captured the imagination of a good many architects of his day and on to the present.

Obedience - “The architecture of a nation is great only when it is as universal and as established as it language”. John Ruskin asserted that England should have one school of architecture, a type of Gothic that was peculiarly English.

The last point touches upon an interesting point within architecture. Various schools of architecture have their own way of looking at things and they are usually quite willing to anathematize anyone who strays from their orthodoxy. Ruskin presents seven lamps that shed light upon architecture. Take his light of “Truth”. There are many buildings that have a certain pretension. They pretend to be something they are not. A Greek Revival house made of wood will pretend to have a great stone entablature, but it does not. With John Ruskin’s lamp we can see it as a fraud and an ugly thing. But view that same building with someone else’s light and we can recognize the beauty and proportion that the wood entablature offers to what is otherwise a humble dwelling.

The architectural concepts presented here are like that. They are paradigms not laws. They provide viewpoints, but in the end most people will not understand the concepts. They will simply look at a building and think “I like that” or “What were they thinking?” They are not an unworthy audience for not understanding the concept. The concept was deficient or it was applied incorrectly, or perhaps there are some things that will always simply be a matter of taste.

John Ruskin's Seven Lamps have inspired much of what is good, and some of what is bad, in the many decades since their publication. What follows is a deeper explanation of his lamps, but Ruskin took dozens of pages to develop these ideas, and I can only offer a few paragraphs.

Sacrifice –Let me borrow from the Bible to explain this. “Do everything as unto the Lord”. Do it well as if you were trying to please God with your design and craft.

Truth – Your buildings should be honest in how they present themselves. No fancy facades hiding poor construction. No wood pretending to be stone.

Power – A building is a shape, a mass. Its immensity in comparison to man has its own effect apart from its ornamentation. The architect’s job is to display this shape to its best effect. Ruskin considers setting and view and line. A building set on a hill can have its mass well displayed. That same building with massive mountains as the backdrop may not seem so consequential. Surround it with buildings and you may find that you can never get your self in a position to see the whole. Ruskin refers to the bounding line and by that he seems to mean an unfettered continuation of an edge, or seam or horizon that the eye will follow. In a Greek temple it is the line of the frieze. If you disrupt that line, you take away from continuity and our ability to take in the mass as a whole.

Beauty – Here John Ruskin refers to skin and ornamentation. He draws heavily on nature, because nature is our school master for beauty. Therefore art in our buildings should be imitative of the forms and lines and shapes we see in nature. If a column seems beautiful it is because we see them all around us in the stems of plants. If a pointed arch is pleasing to the eye it is because that shape was first pleasing as the shape of a leaf. He also castigates some ornamentation that is not imitative of nature, such as the Greek Key, a running spiral design common in some Greek architecture.

Life – This has less to do with the building as it is, but rather the building as it was formed. Building should be made with human hands, and by this he means skilled human hands, masons and carvers and carpenters. The life of the builder must be in the building. Those who build their own houses can relate to this. Ruskin was against the mass production of buildings and any innovation that decreased the skill content of the buildings.

Memory – Buildings (and houses) should reflect the culture and what went on before. They in turn will inform the culture that follows. John Ruskin was not a big fan of innovative disruption. Even gradual change is something to be distrusted. In some ways he was the ultimate cultural conservative.

In a later book, The Stones of Venice, John Ruskin derides classical architecture as “Pagan in its origin, proud and unholy in its revival, paralysed in its old age... an architecture invented, as it seems, to make plagiarists of its architects, slaves of its workmen, and sybarites of its inhabitants; an architecture in which intellect is idle, invention impossible, but in which all luxury is gratified and all insolence fortified.” He gave intellectual justification to those who were looking for alternatives to classicism. He offered them Gothic in its stead. Many architects did delve into the Gothic Revival because of his inspiration, but others took a different route.

While many architects have claimed inspiration by John Ruskin, only a few have embraced all Seven Lamps. Few are willing to be bound to obedience to a style of the past, though they are often not above suggesting their own style as an appropriate object of obedience by others.

The modernists often claimed the lamp of Truth as one of their principles. They often show off the girders and supporting structure, allowing the truth of the materials to shine through. However they generally reject the lamp of Memory, preferring to change the character of an area rather than reflect its values.

The lamp of Life is all but forgotten. John Ruskin valued the contribution of the individual artist and craftsmen. There is little in the way of current building activity, whether modern or traditional, that can be said to draw value from the contribution of its craftsmen. Mass production has won the day.

Power is a lamp that is still burning strong. Skyscrapers are monumental and their mass and shape define them. The best of the postmodern buildings are sculpture writ large.

What is lacking is the lamp of Beauty. The buildings leave an impression from a distance, their size can overwhelm you, even from inside, but its all texture and shape. The minimal detail is inspired by machinery and technology. Nature has been abandoned. You might take exception to the idea that the lamp of Beauty is not valued, but I am applying the term as Ruskin seems to apply it in his book. The beauty that the modern architect offers is distinctly different from what Ruskin espoused.

So why am I claiming Ruskin’s Philosophy as influential in the world of architecture? I will claim two reasons. One, the architects themselves claim this. Two, Ruskin provided a rational for rejecting classicism. He wasn’t the first nor the last, but his was the most widely read and quoted.

As we take a look at the Modernists, and their philosophy, Ruskin is the first step away from the values of the past and towards the brave new world that they promised.

To Top of Page - John Ruskin: The Seven Lamps of Architecture

Forward to Modernist Architecture

Back to Vitruvius and the Ten Books of Architecture

Back to Architectural Concepts

Home

Please!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.