Richardsonian Romanesque

And the Rise of Henry Hobson Richardson

Richardsonian Romanesque was extremely popular at the end of the 19th Century. It is an architectural style that clearly owes its existence to one man.

Henry Hobson Richardson is an architect worth knowing. Not many architects have a style named after them and few have had the impact of H.H. Richardson.

His style is old world, but many of his buildings had decidedly modern purposes. He designed churches, but he also designed public libraries, something relatively new in the world in the late-1800’s. He designed city halls, but he also designed train stations, which had only been around for a few decades when he put his hand to the task.

HHR went to the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris. He learned a great deal about how to put together a beautiful and functional building, but, whereas the Beaux Arts leaned heavily toward the classical model Richardson found inspiration in the Romanesque buildings of Europe.

Trinity Church in Boston was Henry Hobson Richardson’s big breakthrough. It received praise from early on and led to many commissions.

Perhaps because his career only spanned 21 years there is a strong continuity in his designs. It took a few years for his style to develop but it all tends to move in the same direction.

While the bulk of his work would fall under the category of “Richardsonian Romanesque” there are some buildings that could more properly be called Medieval rather than Romanesque. Certainly his most famous houses, the Glessner house and the Watts-Sherman house, aren’t so much Romanesque as they are a high-style Medieval vernacular.

In addition to his Romanesque work Henry Hobson Richardson is also sometimes credited with being influential in the development of the Shingle Style of house. The second article in this series will focus on the houses of Henry Hobson Richardson.

Defining Richardsonian Romanesque

So what is the Richardsonian Romanesque? Like many styles it is poorly defined because so many architects copied parts of the style, but not all, and the term came to cover a lot more than just what Richardson designed.

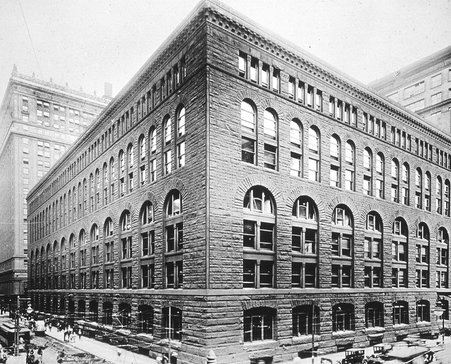

Towards the end of his short career Henry Hobson Richardson was working on developing his “commercial block”. The Marshall Field's Wholesale Store was the result. Though the nature of the work dictated that it maximize its use of space at relatively low cost the walls still look are distinctively Richardsonian Romanesque.

The repetitive arches, formed of radially aligned thin blocks rather than keystones, make up the bulk of the wall. The sill courses underneath the large windows and the top windows and the dentil moulding at the top create strong horizontal lines that emphasize the breadth of the building. From the large windows up their is a progression in sizing, with the penultimate layer having two windows aligned with the large window and four top windows aligned with the two below them. As the window height also lessens this gives the illusion of the top floor being lighter than the lower floors. This keeps the appearance bottom-heavy and stable.

Richardson’s public buildings were generally built of a rough-cut ashlar stone, at least on the lower courses. A rough-facing on the stone gives the stone the appearance of being heavier and thicker than it actually is. On the top-side the roof line was usually continuous, and the roof often was carried down to lower levels. The result was something massive and heavy, but also rooted.

There was usually a dominant axis of orientation, with an entrance along this axis, rather than on the gable end. Stone was laid out in courses of various height which created definable horizontal lines along the exterior wall. His early work was often polychromatic, but later buildings were generally monochrome.

While he used ornamentation to good effect on capitols and throughout the building the exterior walls generally relied on the texture and pattern of the stone.

There was usually at least one prominent Roman arch. Sometimes, as with Sever Hall at Harvard, there is just the one. In other buildings, such as Trinity Church in Boston, the arch is a repeating design element. In some applications the arch is supported by pillars, usually complex Romanesque pillars, but in some cases a combination of Classical Greek and Romanesque pillars.

Above photos courtesy of Daderot at Wikimedia Commons.

Sever Hall has two towers on west facade and two on the east. Brick wasn’t his normal media, but he used it to great effect. The base kicks out in shallow tiers to give a subtle strengthening of the base. Between the floor patterned brick work creates his typical horizontal lines.

Often he lined up arches to create a long series of windows. This created a strong horizontal line, a feature common to most of his buildings.

At times the arch became monumental, dwarfing the other features of the building. Consider the wide Syrian Arches he employed on the track side and entrance sides of the Old Colony Railroad Station at North Easton, Massuchusetts.

Here he did the seemingly impossible, marrying Romanesque and Japanese design ethics into one simple building. The arches are not quite half-round, and the effect is to make the building seem shorter, while the wide eaves give the roof a dominant role and the walls seem to shrink into the shadows. While it probably falls outside the traditional bounds of Romanesque, the large blocks forming the arch place it solidly in the main flow of Richardsonian design.

Photo courtesy of Carptrash at Wikimedia Commons

Towers often buttressed the buildings. Even some of his commercial buildings, like the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building, have towers incorporated into their design. Some are complete towers, others are half-towers, as with the two towers in Sever Hall that flank the entrance from a distance.

On the second floor or higher, there was often a recessed porch, set back behind pillars. On the roof there was often a wide dormer, sometimes rounded rather than flat across.

If we take a look at his houses there is a similarity in form. His shingle style houses, had they been done in granite, would surely be recognizable as Richardsonian. His Queen Anne style houses are less flighty and disjointed than contemporary Queen Annes. His gables and towers are more solidly tied to the house, so that houses seem more massive and more stout.

All of these qualities could be applied by other architects, and often were. Courthouses and public buildings of this era were often Romanesque and often Richardsonian in effect. There were far more Richardsonian Romanesque buildings erected after his death than during his lifetime, as the style remained popular for some years to come.

What his imitators lacked, the one thing that could not be copied, was his eye. There is a certain repose to his buildings that don’t come from the stylings he used so much as how he put them together. I feel much the same way with him as I do about Frank Lloyd Wright. I may not have always like what he was doing, but he did it so well.

Richardsonian Romanesque in Pictures

I will deal with the houses of Henry Hobson Richardson on an another page. I have just told you almost all I know about Richardsonian Romanesque. To finish this story I will let his buildings speak for themselves, with just a few explanatory words here and there.

Enjoy!

Emmanuel Episcopal Church, Pittsburgh, PA, 1883. The church asked for inexpensive. This is what they got. Simple, but stunning. Photos courtesy of Shadyside at Flickr

Austin Hall, 1881, home of the Harvard Law School. It is as functional inside as it is beautiful on the outside. His design for the lecture halls was widely copied for other law schools. Photo courtesy of Daderot at Wikimedia Commons.

Albany City Hall, 1880. The State Capitol building brought Richardson to Albany, but he picked up several commission during the course of that long project. Once again a tower is prominent in his work. This one has a little mini-tower buttressing the one corner of the tower. Photo courtesy of Matt Wade at Wikimedia.

The building below is the New York State Capitol. Henry Hobson Richardson was not the sole architect.He had a partner and they came in after the first architect was fired. Because of cost over runs they were removed late in the project. The building was finished well-after his death, but he is usually credited with providing the bulk of the design.

The Capitol is shown during a recent reconstruction.This shot gives a great overall view. I count eight towers, but one is hidden behind a roof. The facade style is more Renaissance than Richardsonian Romanesque, but the basic plan looks very much like his other buildings.

Photo below courtesy of Skeat78 at Wikimedia.

Free Libraries were a new idea in the late 19th century. The Ames were railroad financiers who took a liking to the Richardsonian Romanesque, so there are several of his building in the town of North Easton, Massachusetts.

Once again credit for the photo goes to the prolific Daderot at Wikimedia

Below is the Converse Memorial Library in Malden, Massachusetts.

The basic "commercial block" concepts he used with the Marshall Field's building are used here. The arch windows become narrower, but more numerous as you move up the building. He would later lose the polychromal look. Note how he uses towers even in his commercial buildings. There is still a strong Richardsonian Romanesque quality to the buildings even though their purpose is so different from his public buildings.

Richardson designed nine railroad stations for the Boston and Albany Railroad. These served both local commuter traffic and the long run to Albany. The building on the left is at Auburndale. This is no longer standing. The one on the right is at Wellesley. It stands, but has been substantially modified. The picture below is the interior of Wellesley. All photos are from the Library of Congress.

Here you can see the variety in sizes he needed to accommodate in his various railroad stations. The station above is the Union Station in New London, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of contributor Pi.1415926535 at Wikimedia.

The photo below is also from Wikimedia, courtesy of Marcbela. It is the station at Framingham, Massachusetts.

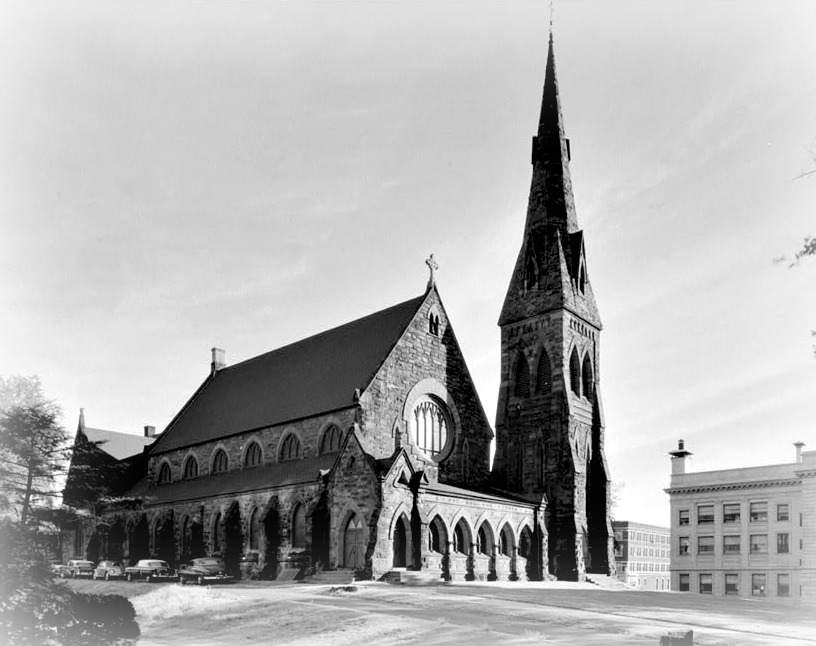

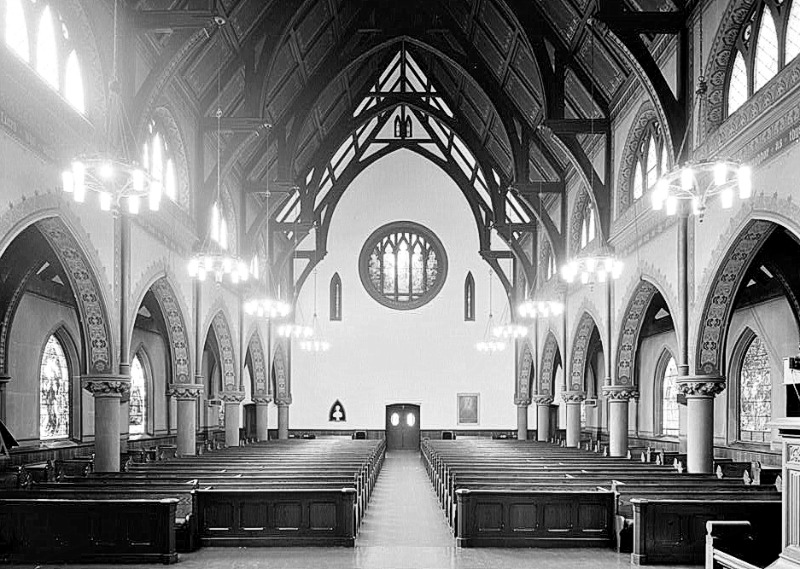

The two churches above and the church below represent Richardson's beginnings. He returns from Europe in 1865, and by November of 1866 he gets the commission for the Unity Church in Springfield, Massachusetts, pictured above. Not long after he gets to build Grace Episcopal in Medford.

They are both Gothic, and of similar appearance. It is an early Gothic, and not far from the Romanesque, so in many ways it looks similar to his later work. They are wide on the bottom and seem broad and stable. While High Gothic could soar these do not, but its not in a bad way. There something humble and quiet about these buildings.

The Unity photos are from the Library of Congress collection of photos. The church no longer stands. Grace Episcopal does and once again I thank Daderot at Wikimedia for chronicling so many great buildings.

During this same period he built some Second Empire homes. This was a very popular style at the time.

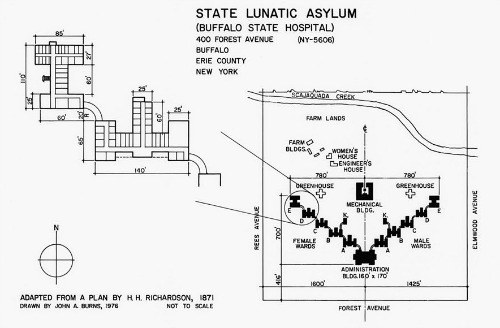

It wasn't until 1869 that he created his first Romanesque building, the New York State Asylum for the Insane.

And here is that first Richardsonian Romanesque building. This was Richardson's largest commission. It grew out of Progressive reformer's desire to improve the conditions for the insane. Many were housed in local jails or the basement of courthouses. Conditions varied but were often not good. Part of the plan of reform was centered around the idea of care in facilities where plenty of light and good views would help cure the patients.

Asylums of that time were built on the Kirkbride plan, which was designed to provide good views for every room. An administration building would have two sets of cascading wings set back from the building. The plan for Richardson's complex is shown below. It is the central building plus five buildings on either wing, with each building connected with a curved corridor. Males were on one wing and females on another.

It also represents Richardson's first venture with Frederick Law Olmstead, the landscape designer.

Black and white photos and plans are from the Library of Congress collections. Color photos are from Flickr's Bobistraveling | |

Designed at about the same time, but finished earlier, the Brattle Square church was also Romanesque, and can also lay claim to being the first Richardsonian Romanesque building, depending upon how you date the buildings. Note the way provides a column as a support for an arch, but backs it up with stone block. The columns were too thin to support the load, but this provides for an elegant front to the archway.

Above is the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh. He also designed a jail, which is much more fortress like. In full disclosure I photoshopped a skyscraper out of the background, which was very distracting. You can see skyscraper reflections on the front of the courthouse.

Photo Courtesy of DearEdward at Flickr.

Below is a shot of the grand staircase inside the courthouse. Thanks to Bruce Coleman at Flickr for the use of this photo.

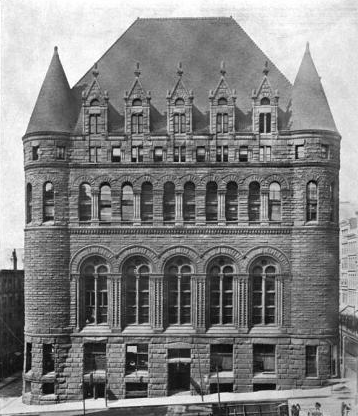

Above is his Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce Building. Coming after his Marshall Field's building many architectural critics consider it a bit of a throwback. The Marshall Field's building seems to point toward the future while the Chamber of Commerce building reverts back to his castle look. Perhaps they are right, but we see some of the same Richardsonian Romanesque tricks used in both buildings. The biggest difference is that the Chamber has a steeply pitched roof, where Marshall Field had a flat roof.

Here is another building from about the time of the New York State Asylum, but this one hasn't fully embraced the Romanesque. The upper windows might be arched, but the roof is like a toned down Second Empire. This is Worcester High School and no longer survives.

To Top of Page - Richardsonian Romanesque

To The Houses of Henry Hobson Richardson

Home - House Design

Please!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.